UTM is an emulator for virtualizing other operating systems. Here’s how to use it to run Apple’s Mac OS 9 on a Mac running on Apple Silicon.

UTM is an OS emulator that lets you virtualize and run a variety of operating systems on other computing platforms, including on the Mac. Based on QEMU, UTM features an extremely minimalist design and is very easy to set up and use.

UTM runs natively on both Apple Silicon and late-model Intel Macs.

Virtualization works by either translating CPU-specific instructions for other processor types to native ones, or by running those foreign instruction sets in software that emulates a foreign CPU. By doing this, virtualization apps let your computer run other operating systems and apps in a process without having to use the native hardware.

For example, you might want to run a version of Windows or Linux on your Mac using x86, x86-64, AMD, or other CPU instruction sets. Virtualization does this by translating or emulating those processors.

The same is true in the other direction: you might want to run macOS or some other OS on a Windows or Linux computer using a virtualization app.

UTM is one such app among many, and it includes a gallery of operating system images you can download and run directly. Or you can set up and configure your own virtualized OS in UTM using the File->New command.

There’s also an iOS version of UTM.

Mac OS 9 and PowerPC

Back in the 1990s, before macOS or Mac OS X, Apple had a different operating system called Mac OS 9.

Apple’s Mac models back then used a RISC CPU called PowerPC created by a joint venture between Apple, IBM, and Motorola. RISC CPUs are generally faster since they contain a smaller set of usable instructions, and thus compiled code is smaller and runs more efficiently.

The first PowerPC CPU Apple used in Macs was named the 601, which was soon followed by the 603 and 604. Later, the PowerPC 740/750 series was introduced, which were faster and used less power.

IBM’s PowerPC 601 CPU – the first PowerPC CPU used in Macs.

The first PowerPC Mac Apple released was the Power Macintosh 6100.

In fact, the very first iMac released in May of 1998 used a PowerPC processor. Later, Apple switched the entire Mac line to use Intel x86 processors before creating Apple Silicon.

The switch to x86 processors also allowed Macs to run Microsoft Windows natively.

Steve Jobs, famously sitting with an original iMac

All of these ’90s model Macs used PowerPC CPUs and ran Mac OS 9. Since Mac OS 9 is compiled into PowerPC CPU instructions, to run it on an Apple Silicon Mac, you need an emulator or virtualization app that can translate the PowerPC instruction set into Apple Silicon, like UTM.

When Apple transitioned from Mac OS 9 to Mac OS X in 2000 it included a built-in version of Mac OS 9 in its own emulator called Classic. That emulator was later discontinued when Apple declared Mac OS 9 officially dead.

Mac OS X was later renamed to macOS as we know it today.

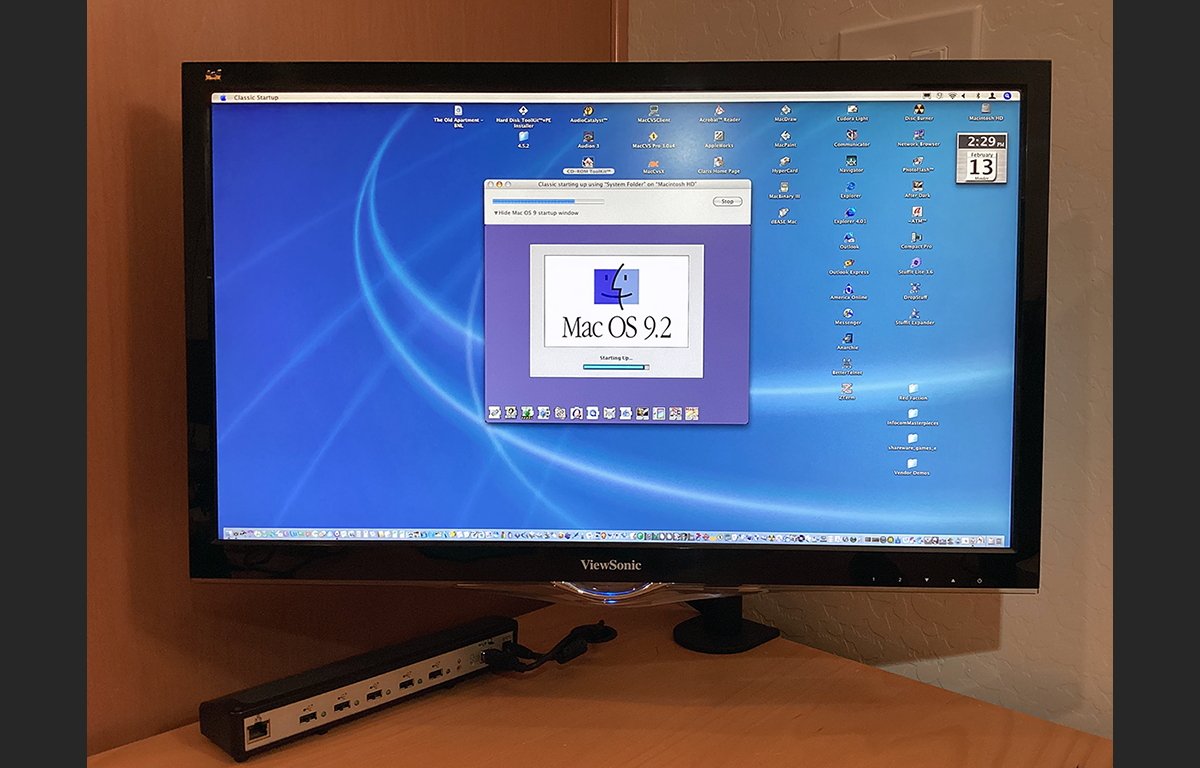

Classic was a huge hit with the very first Mac mini models which were also based on the PowerPC G4 CPU:

Mac OS 9 was a much smaller, simpler single-user OS and wasn’t based on UNIX like macOS is.

Up until now, running Mac OS 9 on Apple Silicon Macs was a bit difficult. There has been a lack of good OS 9 native emulators for Apple Silicon, and there’s little interest today in the PowerPC instruction set, which means there’s little incentive for virtualization app makers to support it in emulation.

But with UT,M that has now all changed.

Getting the original Mac OS 9 installer app to run smoothly without problems on modern Macs has also been a bit challenging. Most Mac OS 9 disk volumes used the Hierarchical File System Plus (HFS+) – which early versions of Mac OS X also used.

HFS+ is still supported today in macOS as “macOS Extended” volumes in Apple’s Disk Utility.

Running Mac OS 9 in UTM on Apple Silicon Macs

For a basic UTM setup, see our previous articles How to use UTM to run almost any version of macOS — even very old ones and How to make boot media for PowerPC Macs on modern hardware.

The second article also contains a brief history of Mac OS, including Mac OS 9 and some photos of Macs from that era.

To install a new copy of Mac OS 9 onto an HFS+ drive, which you can then convert to a disk image to use in UTM, you’ll either need a PowerPC-era Mac or an early PowerPC G4 Mac running Mac OS X and the Classic emulator. You’ll also need a spare drive to install Mac OS 9 onto.

However, there’s now a better and faster way to get OS 9 running on your Apple Silicon Mac without having to run the original OS 9 installer. Through the magic of the Internet Archive you can now download pre-made UTM files containing Mac OS 9 already installed.

To use one of these UTM images, simply download it and double-click it on your Mac’s desktop to open it in UTM. The final retail release of Mac OS 9 from Apple was version 9.2.2.

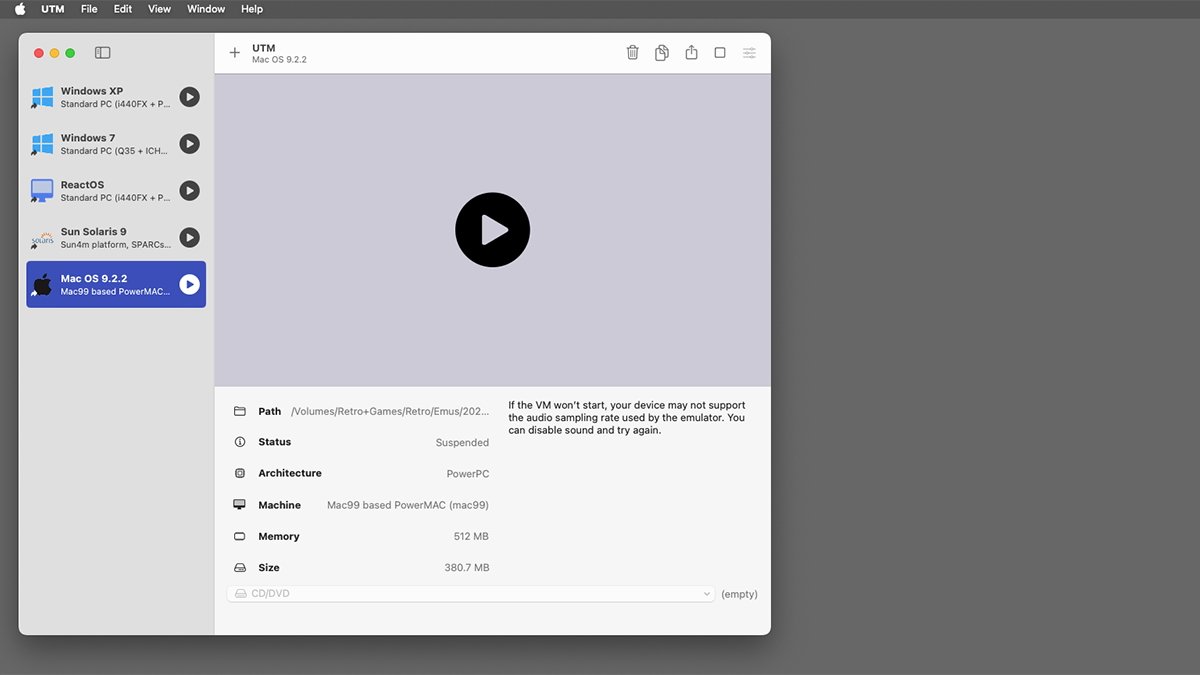

Once you’ve downloaded the Mac OS 9.2.2.utm file and opened it in UTM, a new instance of Mac OS 9.2.2 will be added to the sidebar in the main UTM window.

The Mac OS 9.2.2 UTM file added to the main UTM window.

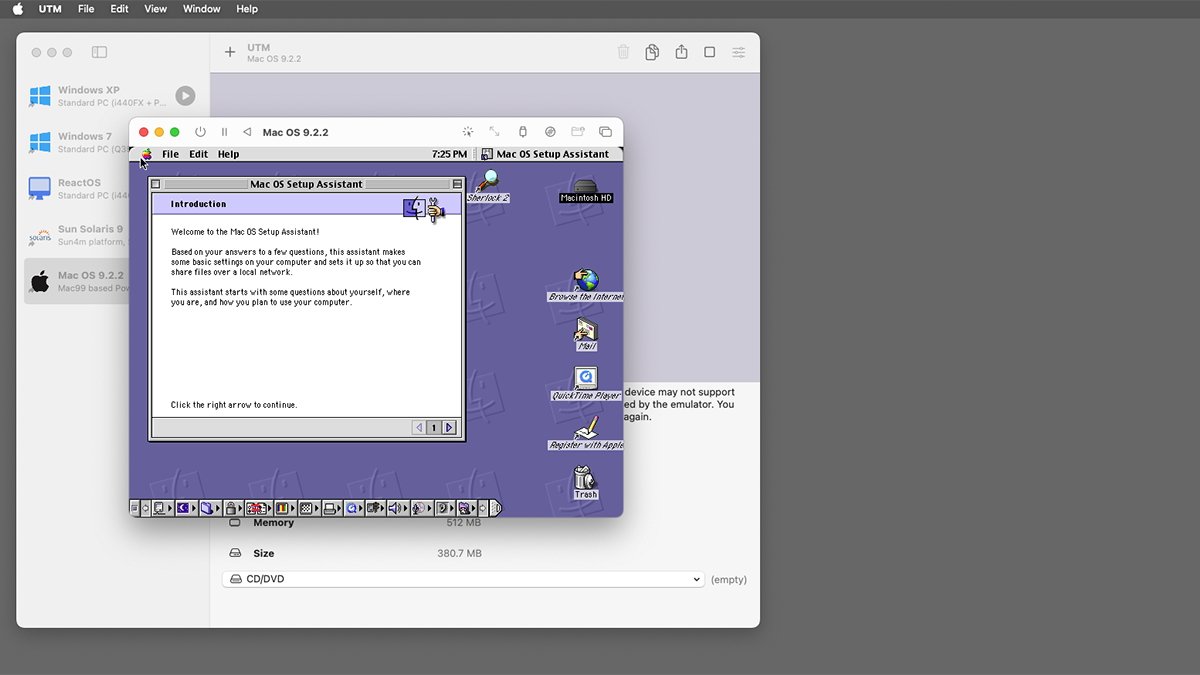

Next, to start Mac OS 9, click the large play button in the UTM window on the right. You’ll see Mac OS 9 boot, and you’ll be left at the default Finder view, just as if you had restarted a real PowerPC Mac running OS 9 after an install.

The small row of icons that appear at the bottom of the window as OS 9 starts are called System Extensions, which patch in additional OS functionality.

You’ll need to step through the initial Mac OS Setup Assistant, which creates default settings for some of the features in Mac OS 9. The small strip at the bottom of the OS 9 desktop is called the Control Strip, which is a little like today’s macOS Dock, but which also provides shortcuts to several OS 9 system settings called Control Panels.

You can disable the Control Strip if you like.

At first, it appears the mouse doesn’t work on OS 9 in UTM. This is because you need to capture it first. Capturing the mouse redirects its input to OS 9 instead of to your macOS desktop.

To do so, click the small cursor icon in the OS 9 UTM window toolbar on the right side. You’ll get the following message when you do:

“To release the mouse cursor, press + (Ctrl+Opt) at the same time.”

When you’re ready to exit OS 9, choose Special->Shutdown in the menu bar, then click the Power off button in the OS 9 UTM window’s toolbar. This quits the OS 9 session.

Mac OS 9 running in UTM on Apple Silicon.

Running OS 9 Internet Assistant Setup

After the Mac OS 9 Setup Assistant is completed, you’ll see another app – the Internet Setup Assistant. Step through these settings, which are mostly self-explanatory.

The one critical setting is the “Configuration Name and Connection Type” pane on which you should click Network (Ethernet/LAN) if your Mac is on a standard network.

On the next pane, “IP Address,” choose No and then click the right arrow button to go to the next pane, “Domain Name Servers”.

Back in the Mac OS 9 days, you had to assign your own IP addresses for DNS. So on the “Domain Name Servers” pane, enter one or more IP addresses of DNS servers to use.

If you know yours, you can enter them here, or use public ones such as 1.1.1.1, or Google’s (8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4).

In macOS, you can view your current DNS server addresses in the System Settings app under Network->Ethernet->Details->DNS. If you’re using WiFi, use Network->WiFi->Details->DNS.

DNS translates web domain names to their corresponding IP addresses.

You can skip most of the rest of the Internet Assistant Setup by clicking the right arrow several times, then finally clicking Go Ahead to finish.

Today’s macOS menu bar was derived from the one in OS 9, but there are some differences. Most obvious is that many of the items in today’s Apple menu in the Finder were originally on the Special menu in OS 9. There’s also no Force Quit menu item in OS 9.

In OS 9 the Apple menu was totally different: it contained aliases (shortcuts) to apps, or to other system folders such as Control Panels, Favorites, and Recent Documents. Printer selection and file sharing was configured in one special OS 9 app called Chooser.

You’ll also notice one odd item in the OS 9 Help menu: Show Balloons. The very first versions of Mac OS didn’t have tool tips like we know them today. So in Mac OS 9 Apple introduced Balloon Help – which was essentially an add-on way to add tool tips to Mac OS 9 apps.

There was even a developer utility called BalloonWriter.

Navigating OS 9’s Startup Disk

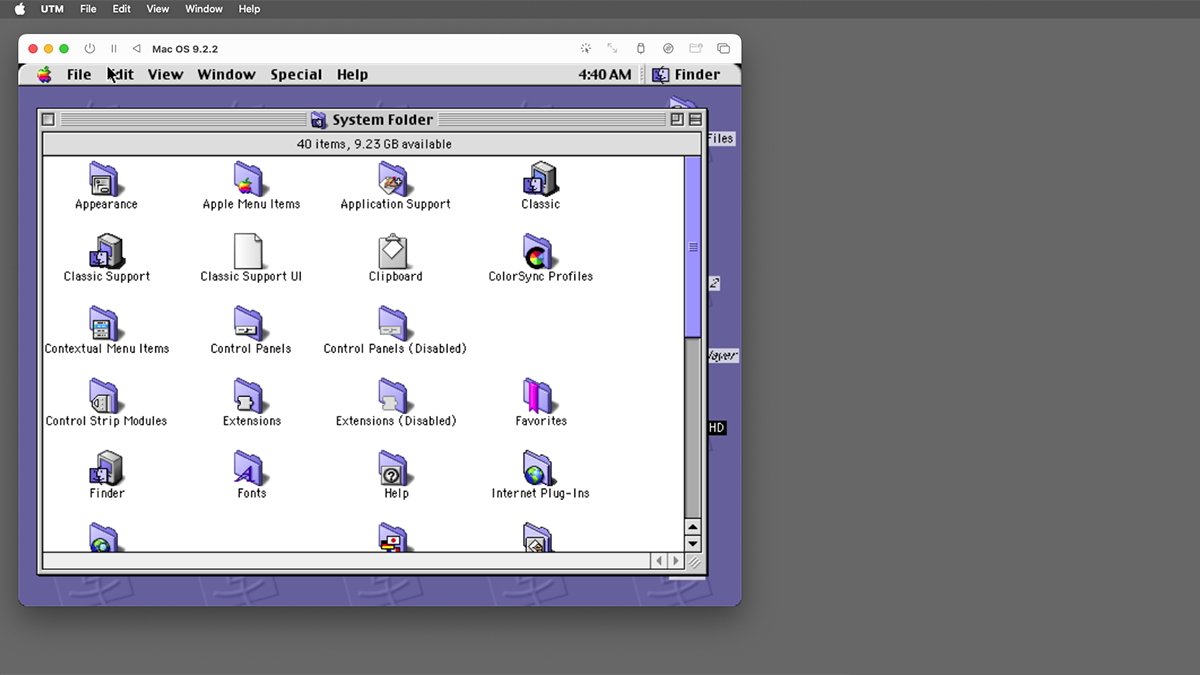

Mac OS 9 was organized somewhat like macOS, but it was much simpler. Like macOS, it had a System Folder, and Applications – but since it wasn’t UNIX, it lacked a Library and Users folder.

By default, OS 9 was a single-user OS, but Apple later added a feature called Multiple Users, which allowed several user accounts to exist on the same OS 9 installation.

To add, remove, or change items appearing in the Apple menu in OS 9, open the Apple Menu Items folder inside the System Folder, and then drag items in or out. You can also add aliases to other items on disk in the Apple Menu Items folder, and they will show up when you click the Apple menu in the menu bar.

There’s no direct way to reorder the items in the Apple Menu Items folder, but a trick we used to use back in OS 9 days was to alpha-order the folder’s items by adding one or more spaces to the beginning of each item’s name. The more spaces an item’s name has, the higher on the Apple menu it will appear.

System Folder/Contextual Menu Items contains additions that get added to the Finder’s contextual menu when you Control-click an item on the desktop. By writing and adding items to the Contextual Menu Items folder, you can extend the Finder’s contextual menu.

Like most OS 9 software, Contextual Menu Items were written in either C or C++.

The next folder, Controls Panels, contains special files used to configure OS 9. Think of these as the various panes in today’s System Settings app in macOS.

Each Control Panel file must contain a code resource of type ‘cdev’ in order for OS 9 to recognize it as a Control Panel.

Every file in OS 9 has a four-character Type and Creator.

Unlike macOS, OS 9 uses these values to uniquely identify files on disk. No two applications in OS 9 can have the same Type and Creator codes.

The Control Panel files themselves have a Type of ‘cdev’ and a Creator of ‘AAPL’.

Mac OS 9 and earlier apps have a separate file fork called the resource fork. Resources have their own Types and an ID number, which are also four-character codes.

The System Folder in Mac OS 9.

In OS 9, Apple reserved all lower-case Type and Creator codes for Apple’s own use. You can view and edit Type and Creator codes using Apple’s own OS 9 resource editor called ResEdit.

If you still have an early PowerPC Mac running an early version of Mac OS X, you can use the FileType app (free).

For a really cool discussion of resources and ResEdit, see the Eclectic Light Company’s The Genius of Mac: ResEdit and resources.

Like System Extensions, some Control Panels can also contain resources to be loaded during OS 9 startup. This is why you may see both System Extension and Control Panel icons at the bottom of the screen when booting OS 9.

The next folder in the System folder is Control Strip Modules. Just as with the Apple menu, whatever items you place in this folder will appear in the Control Strip at the bottom of the screen (after Restart).

But like Contextual Menu items and Control Panels, Control Strip Modules must be written a certain way to be recognized by OS 9.

The Extensions folder comes next, and it contains System Extensions which OS 9 loads at startup. When OS 9 starts, it scans this folder and the Control Panels folder to look for system patches and extensions to load and run.

Every System Extension must contain at least one code resource of Type ‘INIT’ in order to be loaded at startup.

Whatever code resides in each ‘INIT’ resource is blindly loaded and run by OS 9. Hence, it’s very easy to crash OS 9 on startup with a System Extension if it isn’t written perfectly.

‘INIT’ code resources can contain code for additional features, or they can contain Macintosh Toolbox trap patches.

The Macintosh Toolbox was the name given to a collection of standard Mac OS system routines stored in the early Mac’s ROM chips. OS 9 apps would call these Toolbox APIs to execute OS functions, much like Apple’s frameworks of today.

Each Toolbox API had a trap number or address so the system would know how to locate it in the ROMs.

‘INIT’ resources can be loaded from System Extensions or Control Panels at startup to add additional code to each Toolbox ROM API, by patching its trap number or address. Think of an ‘INIT’ patch as an additional bit of code pasted onto the original API. Or in some cases, ‘INIT’ code can replace a Toolbox ROM API entirely.

System Extensions led to some interesting functionality in OS 9 because it allowed developers to modify the core of the OS itself – and change the way the OS looked or behaved.

The Extensions folder also contains a host of other types of files in addition to System Extensions:

- Device Drivers

- Chooser printer drivers

- File Sharing extensions

- Foreign file systems

- PowerPC dynamic shared libraries (code)

- Apple Guide help files

- Modem and serial tools

- Other apps (such as the Print Spooler)

By removing a System Extension from the Extensions folder and restarting the Mac, the extension is disabled. There is no dynamic way to disable System Extensions in Mac OS 9 once loaded, unless one ‘INIT’ resource later disables another one in memory, which was highly unusual.

Most of the other folders in the System Folder are self-explanatory.

One folder, Internet Plug-Ins, contains additions for the first mainstream commercial web browser Netscape Navigator.

Netscape was one of the first dot-com boom companies of the ’90’s which later morphed into the Mozilla Foundation, which today makes the Firefox browser. Netscape’s IPO made its founders Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark overnight billionaires.

OS 9.2.2 includes a copy of Netscape Navigator in the /Applications folder.

The Launcher Items folder contains plugins for a quirky OS 9 app called Launcher. This app never really caught on and was Apple’s attempt to provide a simpler user interface for applications by showing just a single large icon for each app in a window.

To add items to the Apple Launcher, just make an alias to any app on the machine and place it in this folder.

Some of the files in the System Folder and Extensions folder are critical and you shouldn’t move or delete them.

The System file, for example, is required, and if you remove it from the System Folder, OS 9 will no longer boot. The same is true for many of the PowerPC shared library files.

The ultimate OS 9 configurator: Extensions Manager

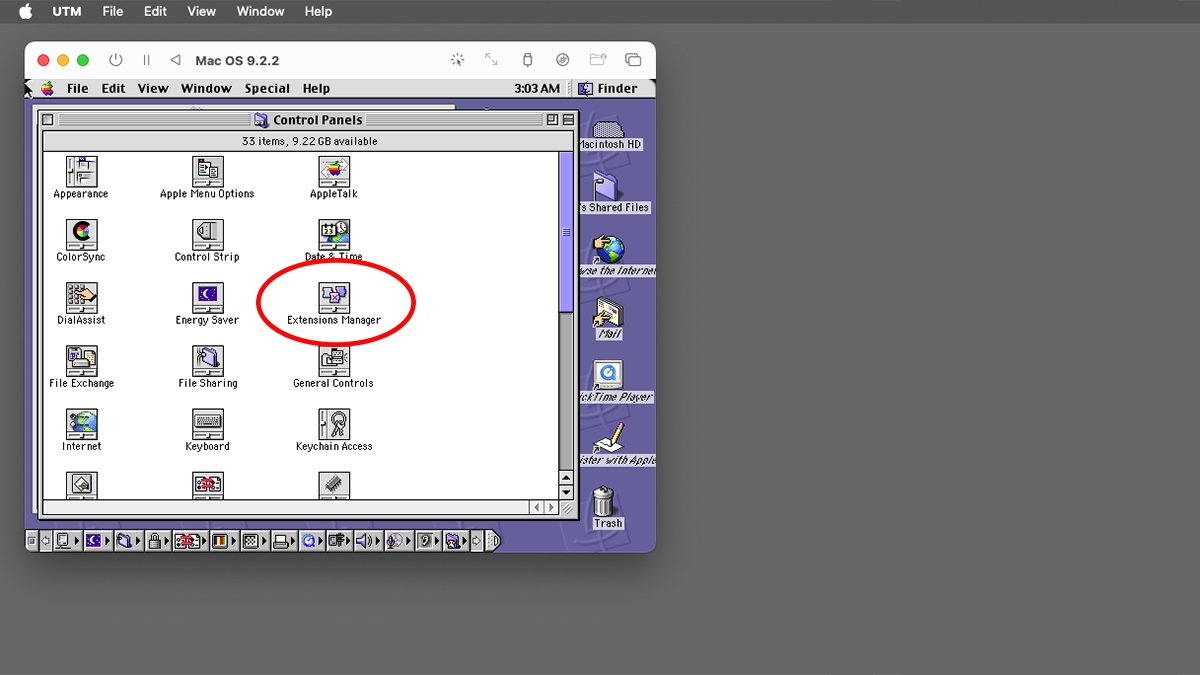

If all of the above about Extensions and Control Panels seems like a hassle, that’s because it was (and is). Apple realized this and so it created a special Control Panel to deal with the chaos called Extensions Manager.

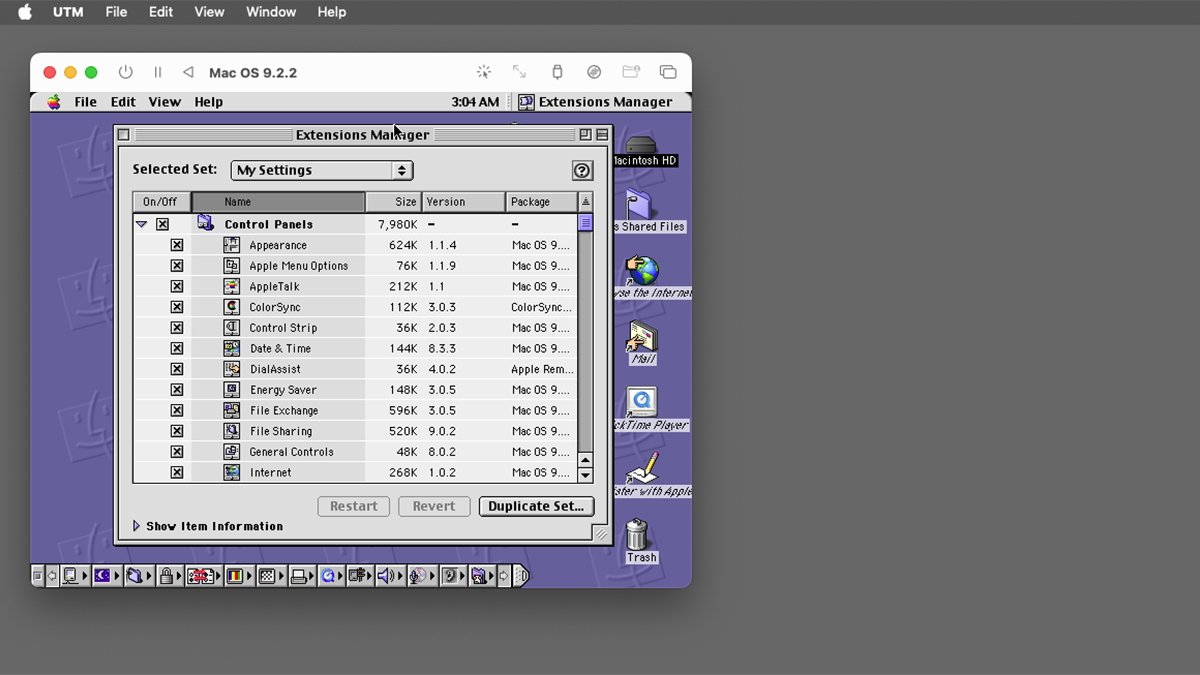

This Control Panel has one purpose: to disable and re-enable System Extensions and Control Panels.

The Extensions Manager control panel in the Control Panels folder.

To use it, you double-click it in the Finder and then click each checkbox next to all the System Extensions and Control Panels on the Mac.

Unchecking an Extension or Control Panel moves it to a disabled folder next to the original folder. Re-checking a checkbox moves the item back to its original folder.

This is a bit janky, but it works. You have to restart after each new set is selected in Extensions Manager for changes to take effect, but it’s a whole lot easier than moving all the files around manually.

One side effect of disabling many of the OS 9 Extensions is that it runs noticeably faster after a restart. This is because all the extra ‘INIT’ patch code mentioned above is also no longer running.

Extensions Manager makes OS 9 more… well, manageable.

Extensions Manager in action. Use the checkboxes to enable or disable each item.

OS 9 apps

Mac OS 9 didn’t include many apps by default the way macOS does today. Mainly this consisted of Navigator, Microsoft Outlook, and Internet Explorer, a DVD player app, and some utilities, as well as AppleScript.

Due to changes in networking standards and protocols over the past twenty-five years, you might find many of the networking features no longer work in OS 9.

Other UTM tricks

UTM has a few other tricks up its sleeve. It seems to do a very good job of scaling the emulator display window without the desktop becoming overly blocky.

For OS 9, however, if you want a larger desktop, don’t resize the UTM window. Instead, go to Apple menu->Control Panels->Monitors and select a larger resolution. UTM is smart enough to resize the window when the display changes size.

You might want to test smaller resolutions first so the UTM window doesn’t resize off the edge of your Mac’s display.

You can also pause and resume emulation using toolbar buttons.

You can set which USB disks to use in Mac OS 9 by using a button in the UTM’s emulator window. But be careful when doing this – remember Mac OS 9 is very old and it may or may not know how to deal with certain volume and file formats on your USB drives.

Overall, UTM is now very useful for Apple Silicon Macs. The fact that you can finally run Mac OS 9 among other OSes in a native emulator for modern Macs is very cool. And its performance is great.

OS 9 runs at least as fast or even faster than it did on one of the late 1990s or early 2000s Macs.