EDITOR’S NOTE: This story references suicide and sexual abuse.

‘Hitting dead ends’

Jeanelle Reanier-Briggs never expected to be fighting for her son’s health while he was behind bars. But as she sat in her Lacey home, reading text after text from her son Kanaan, the reality set in: he wasn’t getting the medical care he needed.

“I was scared he wouldn’t come out,” Reanier-Briggs said. “I felt completely hopeless and helpless as a parent.”

Earlier this year, Kanaan was locked up at the Nisqually Corrections Center for a probation violation. He wrote to his mother about debilitating pain from a back injury, explosive headaches, and crippling neck pain. A hospital visit revealed an aneurysm near his eye, but back in jail, Reanier-Briggs said Kanaan’s pleas to see a doctor went unanswered.

“I’m in unbearable pain … no one has checked on me at all…There’s no doctor here today … There hasn’t been a doctor here in weeks,” Kanaan texted his mother day and night.

The Nisqually Corrections Center did not respond to requests for comment.

The City of Lacey, which contracts with the Nisqually Tribe for jail space, assured Reanier-Briggs that Kanaan was receiving the proper care. But she wasn’t buying it.

She said she began reaching out to the jail, government leaders, advocates, lawyers and others who she hoped could help.

“I was hitting dead ends,” she said. “It controlled my whole life every single day. All I could think of was … am I going to be able to get him the help he needs before it’s too late? Is he going to get worse? Is anybody going to answer me today? … Who else can I call?”

For families with loved ones struggling inside one of the more than 50 local jails in Washington state, there are few places to turn. Unlike at least 26 states, Washington does not have a statewide body overseeing local jail conditions or the treatment of inmates. With no unified jail standards, it’s up to jails to make up their own rules and police themselves.

“It means we don’t know what’s happening inside those jails, and there’s no way to ensure that people inside are being treated appropriately,” said Michele Deitch, a national correctional oversight expert who runs the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas. “They decide what they’re going to do, and the fact is that many jails are not living up to the constitutional minimum when it comes to the treatment of people who are incarcerated.”

Experts, like Deitch, said inmates are paying the price. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington state had the fourth highest jail death rate in the entire country in 2019, the latest year federal data is available.

The KING 5 investigators uncovered cases in jails across the state where, without independent oversight, local inmates faced injustices behind bars.

At the Forks City Jail in Clallam County, a jail guard went unchecked for months in 2019 as he sexually abused five women he was charged with protecting.

In October, KING 5 found multiple Washington county jails – including Lewis, Pierce and Kitsap counties – allowed unqualified medical staff to make pivotal medical decisions about inmates. One of those former inmates, Javier Tapia, lost his leg at the Pierce County Jail after a life-threatening infection went undiagnosed.

“There should be at least a statewide audit system,” said Corinne Sebren, who works as a civil rights attorney for the Washington state firm, Galanda Broadman. “Without that, accountability is very, very difficult to achieve outside of a lawsuit or outside of a reporter digging in.”

Garfield County Jail death prompts calls for reform

One man’s death at the Garfield County Jail in eastern Washington prompted renewed calls for statewide reform.

The county closed its small jail earlier this year after the family of Kyle Lara took legal action, which resulted in a $2.5 million settlement in July.

In April 2022, Lara died by suicide while left alone in his cell, which was located in the dilapidated, neglected basement of the historic Garfield County courthouse. No one discovered his body for more than 18 hours after he took his own life, according to law enforcement records.

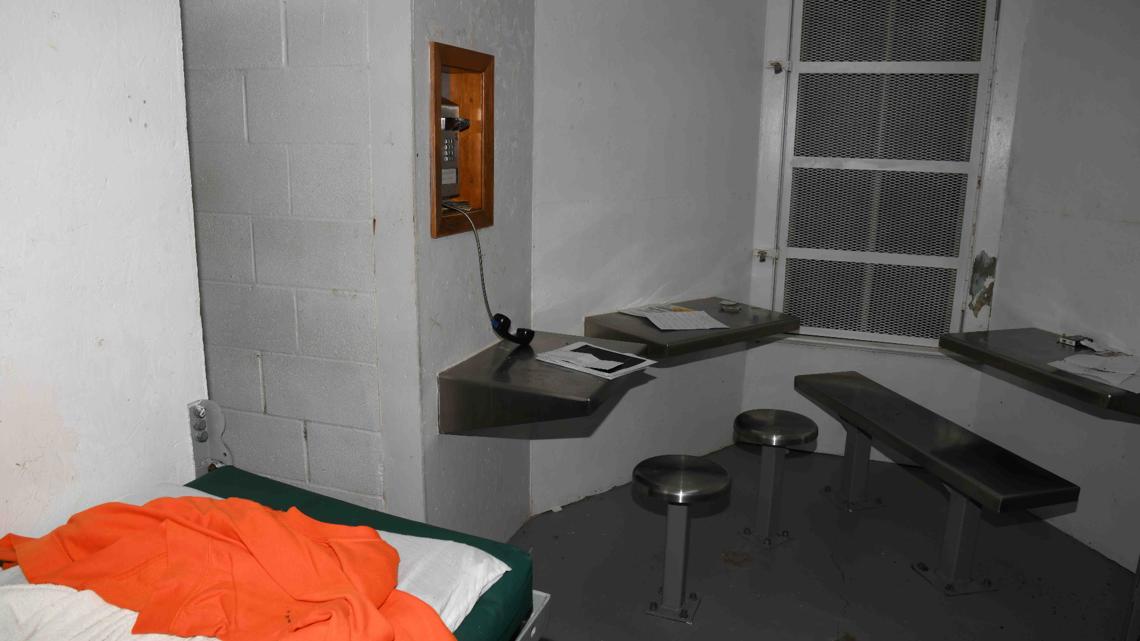

“If there was a state body who had done an audit of this jail, there is no possible way the Garfield County Jail would have passed,” said Sebren, who represented Lara’s family as they filed a tort claim against Garfield County in February 2023. “It was like a dungeon, just paint cracking off all the walls. There’s food strewn about. It’s dark. It’s dank.”

Lara, 36, was awaiting trial when he died. He was arrested about three weeks earlier on domestic violence charges after getting into a fight with his girlfriend.

Garfield County records show Lara had been in and out of the county jail for years, and he was a known suicide risk.

“He should have been on suicide watch,” Sebren said. “I mean, he was expressing active suicidal ideation.”

The jail was not staffed full time. Instead of certified corrections officers keeping a close watch, Garfield County relied on its civilian 911 dispatchers to monitor inmates through video screens as they juggled other duties, like answering 911 calls, dispatching emergency personnel, and entering warrants and protection orders. The dispatchers were also responsible for serving meals and administering medication to inmates.

According to law enforcement records, on the day that Lara died, county jail cameras captured him writing a suicide note and fiddling with an item in his cell that he would use to take his own life. But no one was watching.

The next day, jail staff served Lara two meals while he was already dead.

“Their monitoring of him was just beyond the pale,” Sebren said. “Especially when someone is expressing that they are suicidal. You don’t give them the means to do it, and he had the means to do it in abundance.”

Garfield County Sheriff Drew Hyer, who ran the jail, did not respond to KING 5 inquiries.

Garfield County Commissioner Jim Nelson said there were missteps in Lara’s case, but he insisted the jail was a safe place for inmates. In 100 years of operation, he said, using 911 dispatchers to monitor inmates had been an effective strategy.

“Yeah, there were some failures. We recognize that. You know, some people dropped the ball. The monitoring was part of it,” Nelson said. “It’s a tragedy that this guy lost his life, but … what I don’t want to say is that the jail itself failed. The jail was adequate to safely house inmates, in my opinion.”

Nelson said the small county jail needed more resources. Garfield County, located near the Oregon and Idaho borders, is the smallest county in Washington state by population. The City of Pomeroy is its only incorporated town. The jail was capable of housing up to 16 inmates.

As part of Garfield County’s settlement with Lara’s family, the county agreed to keep its jail closed and instead send inmates to jails in Walla Walla and Whitman counties. Under the terms of the settlement, if the county wishes to open the facility again, it must make improvements, including requiring training for correctional staff.

“Our intent is not to have a jail,” Nelson said. “We don’t have a real need for it when we can contract out.”

Tammi Bragg, a long-time Pomeroy resident who used to monitor Garfield County inmates as a 911 dispatcher two decades ago, said the jail’s closure needed to happen but it came too late. She said there’s a lot for the state to learn from the tragedy in her small community.

“If somebody doesn’t do something, this is just going to keep happening and happening,” Bragg said. “We need standards, and somebody has got to make it happen.”

‘Who pays for it?’

Last year, the Washington State Legislature created an 18-member legislative task force on jail standards that took a deep dive into problems within the state’s jails. The task force recommended Washington establish an independent agency with the authority to make and enforce jail standards.

Earlier this year, Washington lawmakers considered a bill to create an independent jail oversight agency, but the measure failed during the short legislative session.

“It’s long overdue. Washington needs to create a set of enforceable jail standards,” said Deitch, the correctional oversight expert.

This wouldn’t be a first for Washington. In 1981, the state created a statewide corrections board that had the authority to set and enforce jail standards. The U.S. Department of Justice pointed to Washington system as a “model” for other states.

“It was reasonably effective,” said Bill Collins, who worked for the Washington State Attorney General’s Office as the state implemented the board in the 1980s. “There are certain people who would say it didn’t have enough teeth or didn’t use the teeth that it had as much as it could have, but it was at least able – through the inspection process – to remind a particular jail of problems it had and the reports were eventually public documents.”

But in 1987, the state Legislature voted to eliminate the board.

“It’s a shame that the original entity went away,” Deitch said. “A lot of sheriffs feel like this is their domain, and they don’t want some outsiders coming in to see what’s happening inside. But in fact, every public institution needs to be answerable to an outside body.”

Nelson, the Garfield County commissioner, said he’s not opposed to statewide jail oversight, but he’s concerned that lawmakers won’t adequately fund mandatory improvements.

“That sounds good, but who pays for it in a little county like this?” Nelson said. “You can’t put a price on human life, don’t get me wrong. But if the state mandates certain things, then the state would have to step up and fund those because that’s a constant battle for us – unfunded mandates coming down from the state.”

Matt Newberg, Garfield County prosecutor, added he’s worried mandatory jail standards won’t make sense for the unique needs of jails in rural communities like Garfield County.

“A one-size-fits-all statewide requirement is not going to fit in these small circumstances,” Newberg said. “We have a very small law enforcement presence. We have a very small jail. Our daily population is literally zero most days, and so to create a system that checks all these boxes from a statewide standard would likely go unused 99% of the time because we don’t have that need for it.”

Deitch, who has studied jail and prison oversight models across the nation, said it’s important for the state to create an oversight entity that looks at ways for jails to raise the bar when they’re capable of doing more but that also sets a manageable bar for jails strapped for resources to ensure they don’t slip below constitutional levels.

“The cost of oversight is a fraction – a fraction of what we could be spending on expensive lawsuits from loss of life or for other problems, and we are spending so much to operate these jails,” Deitch said. “It’s a drop in the bucket to make sure they’re actually doing what we think they’re supposed to be doing.”

Jeanelle Reanier-Briggs son, Kanaan, is now out of jail. But she said he struggles with trauma from his medical crisis behind bars.

Reanier-Briggs said she deals with her own trauma from her isolating fight to help him.

“It’s like watching your kid drown and not being able to help them. You can’t get to them. You can’t reach them,” she said. ” I expected there to be people who would help — people responsible.”